By

Diane Roberts

Originally

published by Oxford American in their summer 1999 double issue on southern

music

Nice girls were drawn to the Slut Boys like deer to a busy highway: fascinated, frightened, but somehow desiring the fear. The Slut Boys were the most famous garage band in twelve counties, the tsars of the Tallahassee bar scene. They burst forth in a cloud of sulphur and Marlboro smoke in 1979, playing sticky-floored saloons where country boys, disaffected late hippies from Florida State, Izod-shirted private school kids, gay guys in skinny ties, and sorority girls like me would go to drink quadruple bourbon and Cokes, smoke joints in the parking lot, and dance like rhythmically enhanced Pentecostals.

Only, I hardly ever danced at Slut Boys gigs. Not for years, anyway, not until I gave up the Bass weejuns and khaki skirts for the New Wave black of the ‘80s, not until I knew the Slut Boys a whole lot better and figured they wouldn’t kill me (or worse). I used to skulk in back of whatever dive it was that week, watching, scared but enthralled, as the Sluts ground up the stage, covering the Doors’ “Roadhouse Blues” or playing songs of their own like “Mister Stupid” and “No Tomorrow,” leering, jeering, snarling, clutching Budweisers, somehow sending the slam-dancing people up front (the cool people) into Dionysian ecstasies (I was bookish; I really said “Dionysian” to myself), spinning and jumping faster and faster till I, standing still, got dizzy.

It’s no wonder they had pretty much the same effect on nice girls as a couple of shots of tequila. The Sluts were themselves nice, from nice middle-class homes with oak-shaded yards. By daylight, they had proper Southern manners, said “Yes, ma’am” and “No, sir,” and opened doors for ladies. But in the perpetual night inside the bars, they underwent changes of personality and costume, getting into leather jackets and pointy-toed suede boots, revealing their true selves as dirty white boys who could entice cheerleaders, Catholic school girls, even a contingent of Bible class standouts from North Florida Christian High, into shaking what they got on the dime-sized dance floors of liquor lounges in parts of town their parents wouldn’t have believed they knew existed. For the nice girls there was the promise of danger and sex, rebellion of spirit and body (especially body), an invitation to commit apostasy from ladyhood, as the Slut Boys ogled them, shouting,

I

got one hand and it hurts like hell

If

you won’t rock me, somebody will!

If

you won’t rock me, somebody will!

If

you won’t rock me––

“It

was,” says one nice girl fan, “great crotch music.”

Every town has its bar bands, especially college towns with their large populations of pleasure-seeking, disposable-income-squandering children of the suburbs. Every bar band has some sort of following, maybe even a cell of true believers who mean to will their band to the top as a validation of their own hipness. R.E.M. and the B-52s created their cults in Athens’ 40 Watt Club. Hootie and the Blowfish played fraternity parties at the University of South Carolina. Hell, the Pogues used to play formal balls at Oxford University, gobbing on debutantes in taffeta who were slamming too near the stage.

The Slut Boys were different – and I don’t think this just because they were my bar band, my own symbolic, fumbling first steps on the wild side. They had famous fans like U2, Iggy Pop, and Mickey Thomas of Jefferson Starship; played with Joan Jett and the Ramones; and inspired a comic strip called “Mister Stupid,” which appeared in Tallahassee’s alternative newspaper, the Florida Flambeau. They were such stars in Tallahassee, they’d be accosted in every beer barn up and down Tennessee Street. But they didn’t mean to conquer the world, write their Grammy acceptance speeches, get their picture on the cover of Rolling Stone. A couple of them toyed with getting serious, but thinking long-term, making a record, making it big, just wasn’t the Slut Boy project. They played for now, adhering to the seize-the-day (or night) sensibility that was supposed to be the rock ‘n’ roll way. They never hired a manager or an accountant.

There were four Slut Boys: Ben Wilcox had red hair and slim, nervous hands – he played a Vox Jaguar organ and sometimes guitar. He was the quiet one, the one who’d try and calm the disputes that would flare between the other three, but on keyboards he became incandescent himself. Bill McCluskey lit into his guitar like it had offended him, playing as if every song had to be over in sixty seconds. Donny Crenshaw, the drummer, had the Keith Moon moves down, but he was also clever, pushing the Sluts beyond mere bad dude rock to a kind of confrontational cabaret, sharing stage space with blow-up dolls, producing witty posters, and generally exhibiting the results of a well-spent youth reading William S. Burroughs.

As far as the lead singer, Jim Ballard looked like a Botticelli angel and moved like he was some unacknowledged child of James Brown. His stage manner veered precipitously between seduction and punk menace. With Ballard out front shaking the sweat out of his golden hair, voice like fermented honey, the Slut Boys drew pilgrims from as far away as Dothan and Atlanta. They never had a record, but they had their own mob.

Nothing was happening in Tallahassee in 1979. The ‘60s had come late, stayed till about 1975, then departed in a last whiff of patchouli and black light burn, leaving us only disco, lust in Jimmy Carter’s heart, and “Hotel California.” Famous bands didn’t play Tallahassee much, and there were only a couple record stores, no MTV. There were two decent radio stations, WANM (“100,00 watts gone willldddd”), playing the Parliaments and Tyrone Davis, and WFSU, a student station broadcasting from a garret in one of Florida State’s gothic classroom buildings. WFSU introduced a small but determined audience to the Sex Pistols, the Ramones, Elvis Costello, and other artistes off labels like Rough Trade and Stiff. There were letters to the Tallahassee Democrat newspaper yelping about this latest Menace to Youth, these foreign punks with safety-pins through their heroin-pale cheeks, these outside agitators – Tallahassee was ready for the Slut Boys, oh, God, we were ready.

Thinking back on those ur-days, Ben Wilcox says, “It’s the exact same story you’ve heard a thousand times: take boredom, mix it with stupidity, and add a dash of wanting to get laid. We had nothing else to do.”

They had played together in various combinations since 1972, just out of high school. They were more or less nameless until 1979, when they had a gig at the Lucky Horseshoe, a (literally) subterranean lounge frequented by bikers and louche frat guys. They thought they’d call themselves the Soulanoids, but then one day Donny Crenshaw heard a woman he worked with singing “Dirty White Boy” by Foreigner, only she changed the lyrics to “dirty slut boy.”

They infuriated people from the get-go: a Tallahassee women’s group took offense. “Yeah,” says Donny Crenshaw, “about four or five women feminists picketed the bar. They thought we were boys who like sluts, but we were boys who were sluts.”

The name was aggressive and so was the music. Some of the Slut’s early reviews called them “punk.” That wasn’t quite right; it wasn’t wrong, either. They were more like the Ramones than the Sex Pistols, playing so fast they seemed to defy the laws of physics, but screwing with the audience, too, sometimes coming out on stage and just standing there long silent minutes till the crowd starting heckling and begging. Other times they tossed baggies full of what they said was drugs but what was really powdered baby laxative. “The Slut Boys were performance art, prank art,” says Donny Crenshaw.

“I’d say we were just rock ‘n’ roll,” says Ben Wilcox.

Somewhere around 1979 (nobody remembers for absolute sure: those of us in and around the Sluts in those days allow as how our recall, messed with by Bud, bourbon, nicotine, cough medicine, bad marriages, and an unbalanced diet, is somewhat unreliable), the Slut Boys took to playing in a semi-derelict space in a row of little cinder-block storefronts on St. Augustine Street. It was on the edge of the bad side of town, in view of the tall white state capitol building and faux castles of Florida State. They called it the OK Club. We heard that the OK Club’s upstairs used to be a brothel. Maybe the smell of all that anonymous sex drew the Slut Boys – that and cheap rent. They lined the walls with old stained mattresses, tacked a parachute to the ceiling, and played for the hipsters who’d show up to hang out and smash bottles in the street, just to watch cars get flat tires a hundred feet on.

Serious friendships and smoky relationships that seemed at the time to be as profound as Damon and Pythias’s, or Sid and Nancy’s, were forged around the refrigerator at the OK Club. My boyfriend, a skinny comics artist, suddenly looked sexy and dangerous in the humid light of the Slut’s stage. The people from the Flambeau newspaper, people I admired and was shy of and wanted to impress, would smile at me there. In what may later be seen as a minor literary movement, lots of us making the OK Club Colt 45 run turned into journalists and writers. For us, that hot little room on St. Augustine was our Masonic lodge. Eileen Drennen became an editor at the Atlanta Constitution. She says the OK Club “was like the secret hangout.”

Bob Townsend, now an Atlanta-based music critic, says that the OK Club fostered “this strange sense of belonging for people who didn’t belong anywhere. It was combination of the Little Rascals’ clubhouse and hell.”

It

was a good party, too. I’d stand in the back of the OK Club, torn between

feeling desperately cool and terrified that a roach would fall on my head. The

roaches were as big as bats; they lumbered across the tops of the mattresses

and lurked in the dark of the disgusting little bathroom with the sinister

chemical stains, the hookless door, the lurching toilet filled with what looked

like creek water. When I needed to go, I’d sneak out to the Sigma Kappa house,

four blocks away.

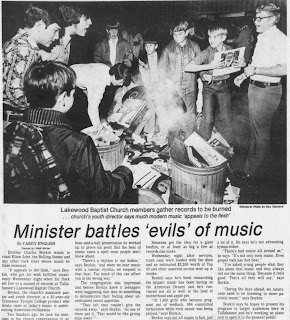

But

bugs or no bugs, I wanted to be there when the Sluts played “Reverend Boykin,”

my favorite. It was a political pop song about a Tallahassee minister who

preached that rock ‘n’ roll was an Engine of Satan and an Incitement to Lust.

The Rev. got a bunch of kids to hurl copies of Sticky Fingers, Led Zeppelin

IV, and Frampton Comes Alive onto a stagey bonfire in front of

members of the local press and a couple of wire services. The photo made page

one in newspapers around the country, but the Sluts took exception. “Reverend

Boykin, you’re right: we’re gonna get loose tonight!” taunted Jim as Donny beat

his drums like a bad dog and Ben’s keyboards shook the OK Club like a

hurricane.

The price of admission to the OK Club was a six-pack or a quart of malt liquor, so Steve Dollar (he’s now the music critic for the Atlanta Constitution but then was features editor of the Flambeau), and I would go over to the Spur on Gaines Street. He says the Slut Boys created “an instant Bohemia – even though none of them, and none of us, were real Bohemians.”

But the Slut Boys and their camp followers didn’t need to be full-bore avant-gardistes to challenge the dominant paradigm, subvert the state, or at least get messed-up and crazy. The stories of Slut Boys exploits still echo around North Florida and South Georgia, part of the underground’s mytho-historic narrative. Some of them are even true.

“My favorite thing,” says Bill, “was when we did Mink DeVille’s ‘Gunslinger’ and when the Slut Boys sang ‘I’ll take you on any day or NIGHT,’ I’d pull out this switchblade. It kind of scared some people.”

Maybe the purest act of barrier-breaking, grownup-scaring, ‘epater le bourgeoisie-ism, was when the Slut Boys played the country club in Grady County, Georgia. Mickey Thomas, the Jefferson Starship singer and Cairo native, heard them at the Crash Landing, a Tallahassee bar. Thomas got them to play a party in Cairo for the (to the Sluts) quite decent sum of $300. It was Grady County Day, and the Slut Boys were driven around Cairo for hours in royal progress by the wild-child heir and heiress of a pickle millionaire, waving at the startled populace like Peanut Queens. They played all night, thanks to the local rich kids, who, apparently, cut the phone lines around there so nobody could call the cops and complain about the noise. The next time they played, to a room full of bourboned-up characters in dinner jackets and Reagan-era red satin at the country club, the police surrounded the area, convinced there was a conspiracy, while the Slut Boys howled out “Stupid is the knowledge that build the pyramids! …I’m Mister Stooopid!”

By 1985 it was over; the band split. The OK Club, where Bono Vox sang “Wild Thing” with the Slut Boys, where I learned to smoke Kools, was torn down a few years later; the place is a raw-dirt empty lot now. And the Slut Boys’ fans have mostly backslid into nominal respectability: journalists, college professors, pickle company executives. It was bound to happen; such immaculate corruption couldn’t last.

I am playing my sixteen-year-old Slut Boys tape, as I often do on a Friday afternoon in Tuscaloosa, with the windows open, so my neighbors – tax lawyers and plastic surgeons mostly – can fully appreciate the guitar solo in “No Tomorrow” and the refrain in “Dogs” that goes “Somebody get me a beer!/Get me a bee-eer!” My doorbell rings, and it’s a kid selling wind chimes. He tells me it’s for a young people’s sexual abstinence program called CHASTE-teen (he spells it for me). “Reverend Boykin” starts up on the tape, the organ like a pile driver. The kid wants me to buy his wind chimes. “Reverend Boykin, you’re right––/You don’t know what it’s like to party like we’re doing tonight!”

The

wind chimes are ugly, little metal blobs that might be flowers, and tubes. “All

right! All right!” sing the Sluts. The kid looks at me. Devil music. “I’m

sorry,” I say, “but I can’t help you.” I shut the door. And I dance.

Thanks to Diane Roberts for permission to reprint this article.

"Till I Can't", a limited edition retrospective Slut Boys LP, will be released by Panhandle Punk Productions in early 2022.